The Concert Ensemble in Kronstadt. January 1942. L-R: Yekaterina Shkroeva, David Pritsker, Arkady Lyzhin, Sofia Preobrazhenskaya, Nikolai Persiyaninov (the Narrator) and Baltic Sea sailors. Preobrazhenskaya’s personal archive

The reverse of the photograph reads “To S. P. Preobrazhenskaya, People’s Artist of the RSFSR from the private staff of Captain Astakhov. In memory of the days of the Great Patriotic War. 22-I-1942”. The renowned singer, a soloist of the Kirov Theatre who also frequently appeared on radio broadcasts, herself admitted that she had an entire collection of similar photographs: Preobrazhenskaya had frequently given concerts for army and naval chiefs even before the war, while during the Siege of Leningrad trips to the front followed one after another. “We performed even when we didn’t have the strength to do so,” the singer recalled, “I remember one concert in the fort at Kronstadt. Ravaged by hunger, Arkady Lyzhin felt as if he were about to drop and, without finishing his aria, went backstage. The same happened with the next performer. The third act was mine: I sang life-affirming songs by Dunayevsky and Pritsker to the accompaniment of the bayan. You should have seen the reception the sailors gave it.”

For Soviet Art. 28 April, 1965. Quote after The History of the Mariinsky Theatre 1783–2008. St Petersburg, 2008. P. 303

The Concert Ensemble. L-R: Vladimir Ulrich (accompanist), singers Sofia Preobrazhenskaya and Vera Shestakova, violinist Alexander Pechnikov; standing: S. Fleishman (the Narrator), a military commander, Arkady Lyzhin. Photograph from 1941–1942

Preobrazhenskaya’s son Vladimir, who was seventeen in 1942, recalled that “After the performance by the artistes the military commanders organised a small dinner for them. Mum (so she said) placed a small open bag on her knees, then put some food in her mouth but, instead of swallowing, dropped it in her bag. When she came home she shared it between us all. Her trips to Kronstadt were a great help to us. After one concert on a ship the commander, discovering that she had four children in Leningrad, summoned the head of provisions and ordered him to give her a loaf of white bread and a kilogram of pasta. <…> Pasta soup and white bread – it was utterly unbelievable, the more so as the bread had been baked from flour that divers had salvaged from the food stores in the bow of the battleship Marat that had been split open and flooded. <...> Another time mum took one of her two silver fox furs and exchanged it for a small bag of rye.”

V. Gureyev. Memories of S. Preobrachenskaya // http://preobrazhenskaya.com/publikatsii/vospominaniya/category/323-v-n-gureev.html

The Concert Ensemble of Kirov Theatre performers. L-R: Alexei Rastorguev, Mikhail Ratner, Vladimir Yekimov, Solomon Kafian. Alevtina Kholmina singing. 1942

The Kirov theatre would regularly send such ensembles to Perm “for the cultural enlightenment of soldiers, commanders and political workers”, as the newspapers wrote at the time. The ensemble headed by the cellist Mikhail Rikhter performed on the North-West front from late January to mid-April 1942, giving over eighty concerts.

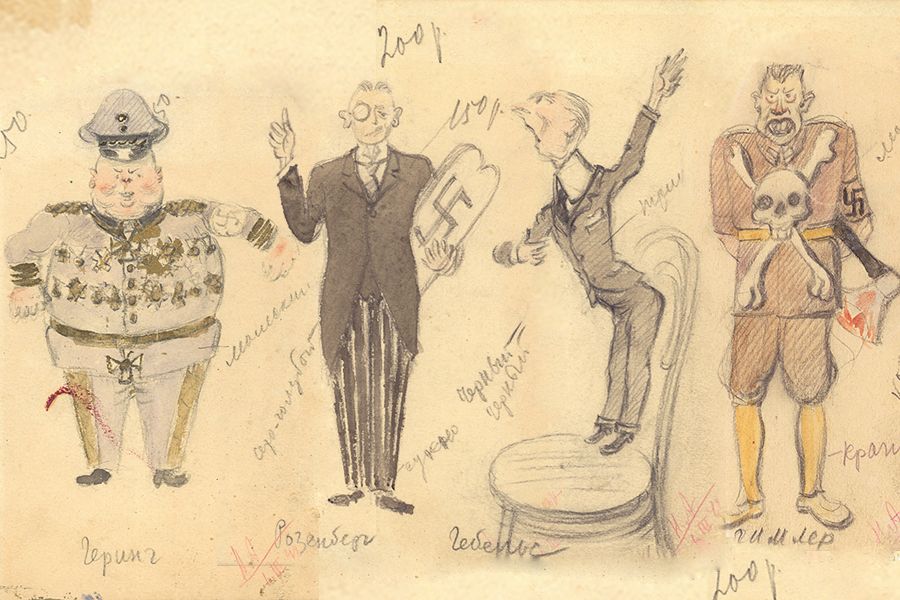

Sketches by Nathan Altman for a concert on 12 March 1942

Nathan Altman and his family were evacuated to Molotov along with the theatre, and on 1 October 1941 he was asked to be Principal Designer*. As all the sets had remained in Leningrad, he basically had to redesign from scratch the sets for Faust, Prince Igor, Dubrovsky by Nápravník and Laurencia by Krein as well as the operas Into the Storm by Khrennikov, Shchors by Fardi and Three Encounters by Khodzha-Einatov.

In Molotov there were performances almost every day, and there were also frequent night-time concerts. In just the first six months the company had performed eighteen different operas and ballets. At the same time, new productions were being rehearsed.

* Employee’s personal record form. Mariinsky Theatre Archive

The public at the Pushkin Drama Theatre. Leningrad. 1942

In besieged Leningrad in January and February all performances and concerts were cancelled and the artistes sent on leave without pay. But on 1 March 1942 a decree was issued stating that the singers Pavel Andreyev, Natalia and Pavel Bolotin, Maria Zyuzina, V. Pavlovskaya, Ivan Pleshakov, Sofia Preobrazhenskaya and Vasily Sorochinsky, the dancers Yevgenia Gempel, Nadezhda Fyodorova and Tatiana Shmyrova and the chorus members Glafira Nikiforova and Tatiana Kholmovskaya be recalled from their leave and come to work. The company was joined – from the Maly Opera Theatre – by Nina Velter and Vera Shestakova. This was done “in connection with organising concerts to entertain the Red Army and the Fleet as well as the population of Leningrad.” Bread brought in via the Road of Life and electricity produced at the Utkina Factory’s power station meant the theatre had a supply of electricity, and it was the intention of the city authorities to support the besieged and beleaguered city residents by reviving musical productions in the city.

Buying tickets at the Pushkin Theatre. Spring 1942

On 3 March the Musical Comedy Theatre revived its performances at the Pushkin Theatre.

On 5 April there was a concert with Kirov Theatre performers Pavel Andreyev, Ivan Nechaev, Vera Shestakova, Vladimir Kastorsky and Nadezhda Velter to open the philharmonic season. The Radio Broadcasting Committee Orchestra was conducted by Karl Eliasberg. The concert was broadcast on the radio. “In the first half Kastorsky sang Susanin’s aria and I sang the aria of the Maid of Orleans,” Nadezhda Velter recalled. “I asked my husband (Georgy Tsorn, a Kirov Theatre designer – Ed.) how my voice sounded. ‘I wasn’t really listening,’ he replied, ‘I couldn’t take my eyes off your terribly thin faces.’”

N. Velter. About the Opera House and Me. Leningrad: Sovietsky Kompozitor, 1984. P. 137

Concert Ensemble. June 1942

Another photograph from Preobrazhenskaya’s archive. The ensemble’s performers include Pavel Andreyev (third from left) and Ivan Nechaev (third from right). Ivan Nechaev’s voice was well known to all residents of Leningrad. From the start of 1942 the singer had appeared on Sundays on the radio together with bayan player V. Kozhenkov from the Ensemble of the Red Banner of the Baltic Sea Fleet. He himself conducted the concert by requests, naming the works and at whose request they were being performed. At the end of the concert he turned to the audience, stating that they should send their requests to the Radio Committee. Generally, the wounded and soldiers on the front asked for Russian folk songs to be performed. “Mentally I often transport myself back to that terrible time,” wrote one siege survivor later. “I see myself, starving, exhausted, I see my wife, daughter and son, I hear the screaming sirens, the evil drone of the German planes, the squeal of incendiary bombs. It was all death and destruction. But after the air raid alarm was over we could once again hear the voice of the presenter – ‘And now we’ll hear Ivan Alexeyevich Nechaev.’”

* Quote after: A. Kryukov. Music during the Siege. Chronicle. Leningrad: Kompozitor, 2002. P. 90

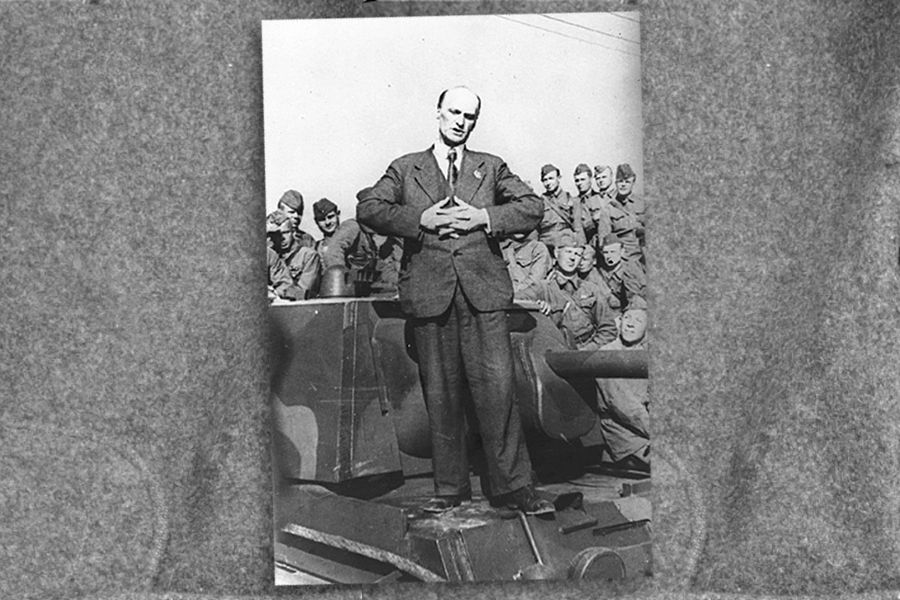

Pavel Andreyev. 25 June 1942

Pavel Zakharovich Andreyev was one of those Russian singers who combined in his artistic career the great past of the Mariinsky Theatre and a theatre that took a new name but inherited old traditions. He was one of few to have sung before Russian soldiers during both the First and Second World Wars. His characters onstage were Russian bogatyrs – Prince Igor, Ruslan and Stepan Razin. A unique case in theatre history came when Fokine was staging the ballet Stepan Razin to the music of Glazunov’s symphonic poem – he invited the opera singer to perform the lead role. Andreyev sang as Boris in Boris Godunov alternately with Chaliapin, and in the 1911–1912 season in Chaliapin’s production of Khovanshchina at the Mariinsky Theatre he created an unforgettable image as Shaklovity. “The audience waited and was dying in suspense when Andreyev as Shaklovity sang ‘The nest of streltsy is asleep. Sleep, Russian people. The enemy is not watchful,’ recalled the academic Dmitry Likhachev, who had seen Andreyev as a boy onstage in 1918. “The audience arose when Andreyev concluded his monologue with a prayer: ‘Oh, God, take away the sins of the world, hear me, do not let Russia perish at the hands of evil mercenaries.’ Andreyev would sing this aria up to three times – the audience demanded encores. Many cried.”*

When the board decided to evacuate the company to Molotov (Perm), Pavel Andreyev and his wife Lyubov Andreyeva-Delmas categorically refused to go: “All of the performers must not leave the city: who will entertain the fighters in their brief hours of leisure and inspire them to feats of arms? If I have to then I have enough courage and strength to take up a rifle.”**

He sang in dug-outs, in the forest and in the fields whatever the weather, and in ferocious minus 30°C temperatures. When he sang the steam poured out of his mouth, risking his beautiful voice.

* D. S. Likhachev. Memoirs. St Petersburg. 1995. PP. 93–95

** Quote after D. Lebedev. P. Z. Andreyev. An Outline of Life and Artistic Activity. Leningrad, 1971. P. 53

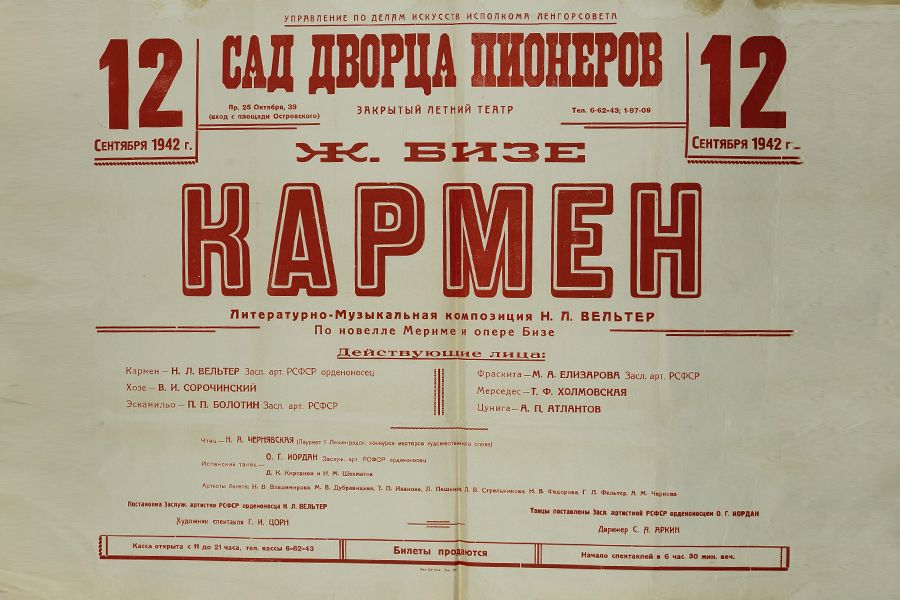

Nadezhda Velter as Carmen. 1942

Programme of premiere performances of Carmen at the Leningrad Philharmonic. July 1942

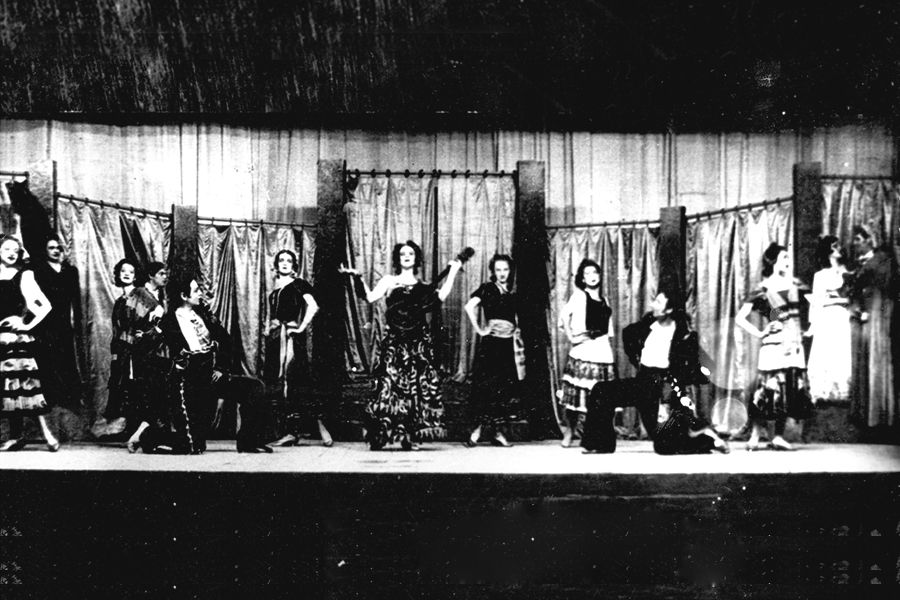

One highlight of cultural life in Leningrad under siege was a production of the opera Carmen. More precisely, it was a music and drama composition: the singer Nina Chernyavskaya read extracts from Mérimée’s novella, interspersed with parts of Bizet’s opera. The production was staged by the singer Nadezhda Velter. After the departure of the Kirov Theatre’s Deputy Director Alexander Belyakov to Perm it was she who directed the members of the company who had remained in town.

Carmen. Scene from the opera. Photograph from 1942–1943

“As there was no orchestra pit in the Philharmonic,” Velter recalled, “the musicians were placed in the two side boxes to the left. As the director I had to take into account the performers’ physical condition, especially the chorus (the Radio Committee Chorus was performing – Ed.). Many were so emaciated that they could only sing sitting down. <...> Those who were able to came closer to the public, and we soloists had to make a great effort using make-up and costumes in order to look like happy Spanish people. We were worried that firing or an attack would stop us beginning the performance on time and so everyone involved – singers, dancers, musicians, make-up artists and lighting technicians – had arrived five hours before the start. <...> At the very first notes of the overture the audience was a sea of white handkerchiefs – the audience were wiping tears of joy away.”

N. Velter. About the Opera House and Me. Leningrad: Sovietsky Kompozitor, 1984. P. 137

Carmen. Performance poster. 1942

In just the summer of 1942 the opera was performed ten times at the Philharmonic, the House of the Red Army, the House of the Fleet and at the summer theatre of the Palace of Pioneers.

Nadezhda Velter at the Blood Transfusion Institute. 1942

Singers Nadezhda Velter, Sofia Preobrazhenskaya and Nikolai Gladkovsky and pianist Marianna Gramenitskaya became donors in 1942. “I’ve had a blood transfusion,” Velter quotes in her memoirs from a letter from one of the wounded, “and now I’m off to the front. I’d like to know – are you the Honoured Artist who so frequently comforts us soldiers with your art? How happy I would be if I knew that within me was an entire bottle of your blood.”

N. Velter. About the Opera House and Me. Leningrad: Sovietsky Kompozitor, 1984. P. 137

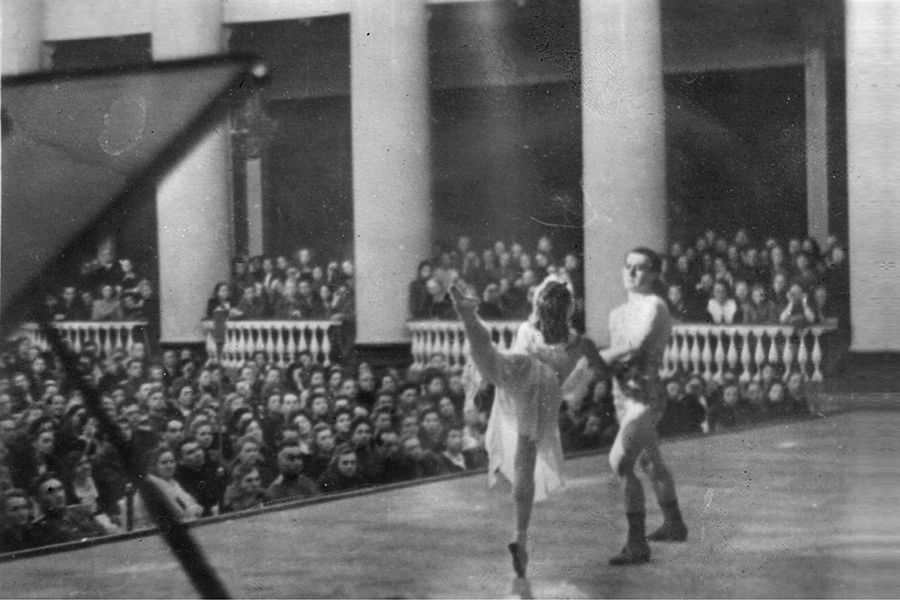

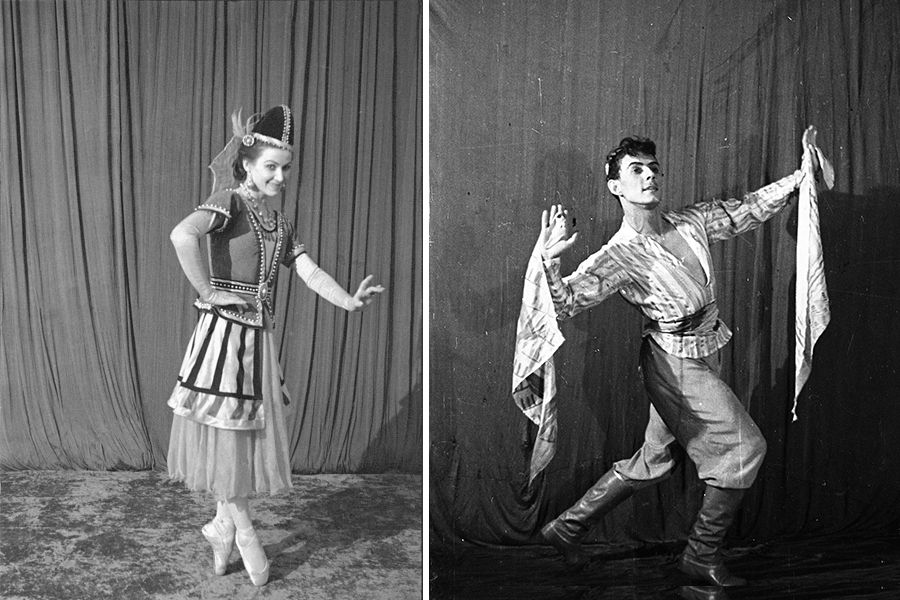

Natalia Sakhnovskaya and Robert Gerbek at a military base. 1943

The dancers Natalia Sakhnovskaya and Robert Gerbek, who, like many other performers after the company had been evacuated, had been sent on unlimited leave were “back to work to provide concerts for sections of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army”* in spring.

This was how Sakhnovskaya described their first performance: “There was a tiny stage in a large room and the audience was a small group of people in overcoats and quilted jackets, drivers who had undertaken many journeys across Lake Ladoga. The long forgotten stage-fright was like returning to life. But can we dance and will the audience watch us? We have changed so much.

The costumes are loose, we have to wear long gloves over our arms and capes on our shoulders. I wanted somehow to ‘screen’ my aged face... Familiar bars of the music. My heart was beating wildly and we nervously went onstage... My legs found it hard to keep up with the music, just a few movements, and we were almost exhausted. My head was spinning, it was as if it was getting dark, several times we collided, barely able to remain standing. Fortunately I was ‘as light as a feather’ and Robert Iosifovich was able – with a little trouble – to lift me. I wanted it to be over but we had to keep going! But what a joy the applause was! Applause. The people need us!!!”**

* Robert Gerbek’s registration card. Mariinsky Theatre Archive

** N. Sakhovskaya. Memoirs. From the Ballet Dancer's Diary // Soviet Ballet. 1983. №3. P. 58

Concert by Natalia Sakhnovskaya and Robert Gerbek at the Leningrad Philharmonic. 31 October 1942

Continuation of Sakhnovskaya’s memoirs: “The Philharmonic offered Robert and me the chance to perform a duo concert in the Great Hall. We agreed and, in between work with the ballet company and concerts for military commanders, we began to rehearse for this important encounter with the audience. It took place on 31 October 1942. About four in the afternoon we arrived at the Philharmonic and stood rooted to the ground: the door was shut. In one and a half years the administration had simply forgotten that we need time to prepare. The woman on duty came half an hour before the concert. It was pointless being angry, and we couldn’t get nervous – it would mean less nervous energy for the rest of the evening. We sat down on the steps of the grand staircase. We began to do our make-up. (...) I don’t remember when they opened the door... I only remember standing behind the heavy velvet portières of our beloved Philharmonic, and when the portières were swept back we stood on the lit stage.

In a trice our fears and anxiety had disappeared, replaced with joy, tremendous joy... Never, it seemed, had we danced with such pleasure, never had we felt such a complete response. The gentle faces and warm welcome were our rewards... We were asked to repeat the concert but the freezing weather had arrived and the hall was not heated. It was only in 1943 that we were able to repeat our programme at the Philharmonic and in the Leisure Park.”

N. Sakhovskaya. Memoirs. From the Ballet Dancer's Diary // Soviet Ballet. 1983. №3. P. 59-60

25 October Prospekt (Nevsky Prospekt). Outside the Comedy Theatre. 1942

In the spring of 1942, when the city was slowly coming back to life following the incredibly harsh first siege winter, the authorities came up with the idea of organising a City Theatre where there would be performances of plays, operas and ballets. That took up the spring and summer months – most difficult of all was to assemble a chorus and orchestra. The City Theatre opened in the premises of the Comedy Theatre on 18 October with Russian People after the play by Konstantin Simonov. Thus (unofficially) did the people of Leningrad who had remained in the city under attack from bombing and artillery strikes commemorate the first year of the siege. The opera company, formed from artistes of the Kirov and Maly Theatres who had remained in the city, was headed by Ivan Nechaev.

Playbill for premiere performances of the opera Eugene Onegin. Leningrad. November 1942

To mark the 25th anniversary of the October Revolution a premiere of Eugene Onegin was announced. The opera was staged by Pushkin Drama Theatre actor Yevgeny Studentsov with the chorus and orchestra of the Radio Committee conducted by Karl Eliasberg for whom it was his first opera. The day before the premiere the scene of the ball had been broadcast on the radio.

Maria Merzhevskaya (Olga)

Maria Yelizarova (Tatiana), Andrei Atlantov (Gremin). City Theatre. 1942

Listed on the playbill alongside the names of acclaimed opera singers – Preobrazhenskaya, Nechaev and Legkov – was the name of the twenty-two-year-old Maria Merzhevskaya, who joined the company on 30 September 1942.

In the photo on the right: Andrei Atlantov (Gremin) declares his love for his wife Maria Yelizarova (Tatiana). Today’s audiences will be more familiar with their son – Vladimir Atlantov, a famed tenor and People’s Artist of the USSR who has been made an Honorary Kammersänger of the Wiener Staatsoper.

The ball at the Larins’. R-L: Maria Yelizarova (Tatiana), Ivan Nechaev (Lensky), V. Boginycheva (Larina), Maria Zyuzina (Olga), Valentin Legkov (Onegin), Glafira Nikiforova (the Nanny), Nikolai Shekhmatov (a Guest). 12 November 1942

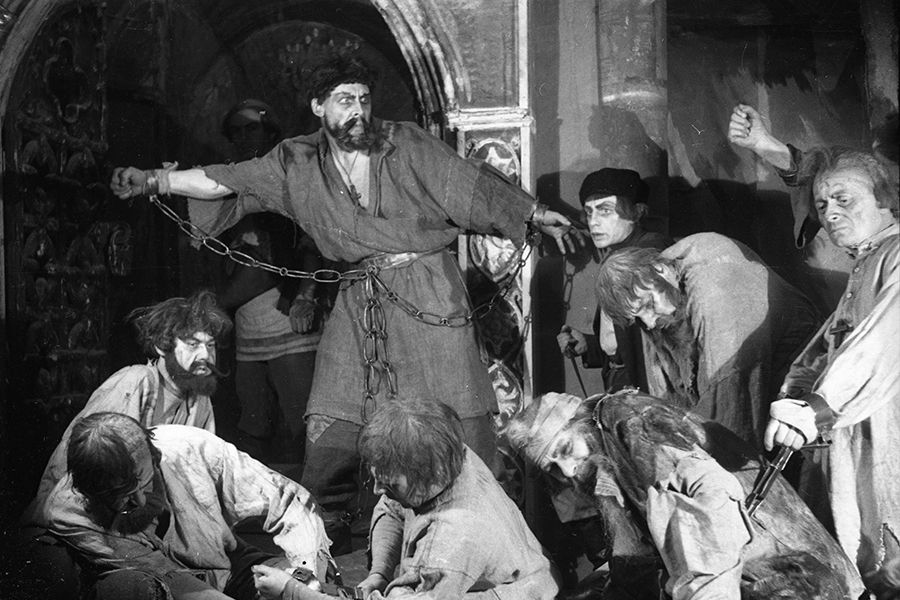

Emelian Pugachov. Scene from the opera. On the left: Ivan Yashugin (Pugachov). Molotov (Perm). 1942

In Perm the premiere of Marian Koval’s opera Emelian Pugachov was to be dedicated to the November holidays. During the War plots on heroic battles with the enemy – from Ivan Susanin and Prince Igor to Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky – were in particular demand. In accordance with Soviet ideology, the image of Pugachov in the opera was made heroic, Pugachov’s resistance staged as a folk uprising. Koval – formerly an active participant of the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM) – did not disguise his attachment to the so-called democratic movement in music. A composer of songs and song cycles to verse by Soviet poets, for several years he was Artistic Director of the Russian National Pyatnitsky Chorus. For the opera he was only able to compose the piano score, which was orchestrated by Dmitry Rogal-Levitsky, a professor at the Moscow Conservatoire, a brilliant connoisseur of the orchestra and author of theoretical treatises on instrumentation. Critics noted the lack of correspondence between the “splendidly picturesque and somewhat ‘French’ colour of Rogal-Levitsky’s score and the form of Koval’s music – at times deliberately boorish and primitive in terms of harmonies.”*

* V. Bogdanov-Berezovsky. The Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre. Leningrad–Moscow, 1959. P. 212

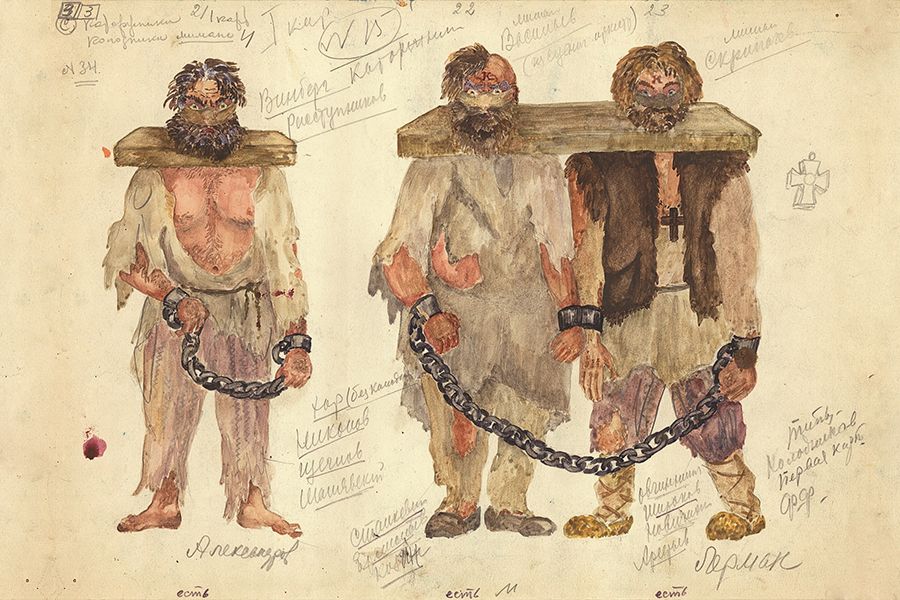

Fyodor Fedorovsky. Sketches for the opera Emelian Pugachov

One of the finest elements of the production, it was generally said, was Fedorovsky’s set designs, with his meticulous knowledge of aspects of time, quite heroic in terms of its tone.

Emelian Pugachov. Scene from the opera. Molotov (Perm). 1942

For this opera, in 1943 Marian Koval was awarded the Stalin Prize, 1st class. One typical detail of the war years was the fact that the composer donated the money part of the prize to the Defence Fund.

Xenia Zlatkovskaya, Aram Khachaturian and Tatiana Vecheslova. Molotov (Perm). 1942

The next premiere by the theatre was to be the ballet Gayaneh, which they had begun to rehearse while still in Leningrad. It was staged by the brilliant character dancer Nina Anisimova. Aram Khachaturian travelled to Molotov to complete the score.

“I remember that I spoke with each performer of the solo roles, how at rehearsals I dismembered the music of each variation and each dance duet so that the dancers could clearly see the idea and the meaning,” recalled Aram Khachaturian.

“Quite often we met with Khachaturian to have a laugh and a joke,” wrote ballerina Tatiana Vecheslova who performed in the premiere, “Once he treated us to a bottle of red wine that had been mysteriously preserved – at that time is was an unheard-of rarity.”

A. Khachaturian. Choreographic Amplitude // Konstantin Sergeyev. Anthology of articles. Moscow. Iskusstvo, 1978. P. 187

Tatiana Vecheslova. I Am a Ballerina. Leningrad-Moscow. Iskusstvo, 1964. PP. 144–145

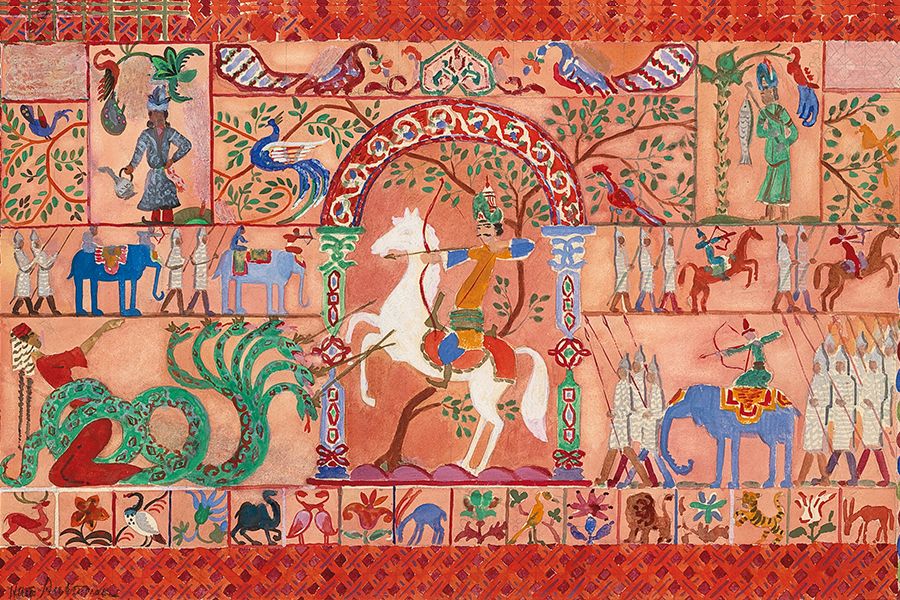

Nathan Altman. Sketch for the curtain for the ballet Gayaneh

Altman designed the curtain which depicted knights-of-old, while on the stage the backdrop showed mountain ridges and cotton fields. At the theatre there was a joke:

They say that on Lake Sevan

They know little about Nathan.

But then probably Nathan

Knows little about Lake Sevan!

Tatiana Bruni was the costume designer.

Tatiana Bruni. Sketches for costumes for a Kurd and Gayaneh

Nikolai Zubkovsky (Karen) and Tatiana Vecheslova (Nune)

The premiere took place on 9 December 1942. Nina Anisimova wrote in the theatre’s in-house newspaper: “On the days when the premiere is being rehearsed the Fascists are attacking Trans-Caucasia. Our production is a fraternal message of support to the heroic peoples of the Caucuses.”

In the finale the ballet’s protagonists are Armenian collective farmers standing next to loudspeakers listening to the news of the German aggressors invading Soviet lands. The mischievous Nune and Karen, their roles performed by Tatiana Vecheslova and Nikolai Zubkovsky, were the first to leave for the front. The audience saw them off with warm applause. A new version of the ballet with a different finale appeared once the company had returned to Leningrad.

For Soviet Art, 1942, No 6

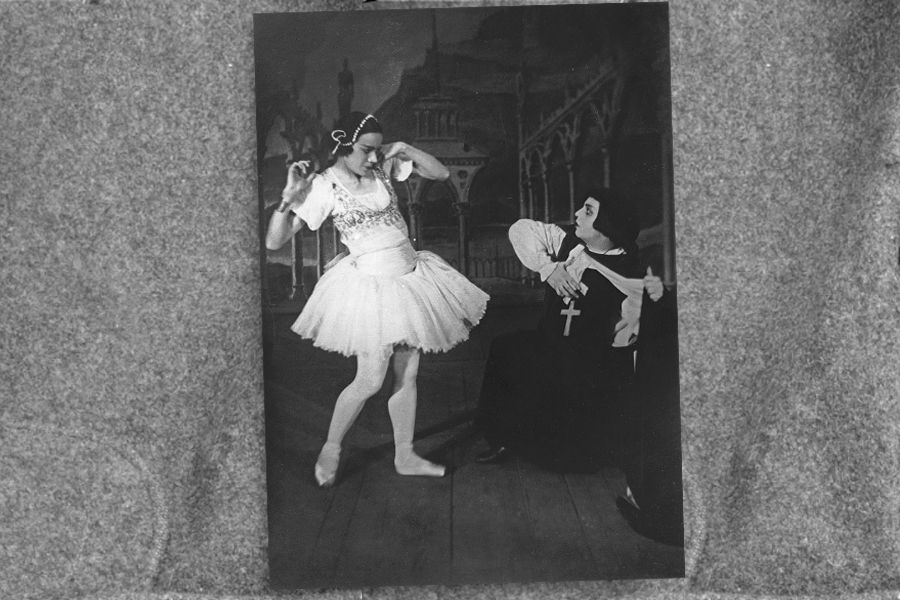

Scene from the ballet La Esmeralda. Leningrad. City Theatre. 1942–1943

For the siege theatre the last premiere had been La Esmeralda, staged at the Comedy Theatre on 18 December 1942.

The production was revived by Olga Iordan, who was combining her duties as Artistic Director of the ballet company, ballerina, choreographer, teacher and coach. For the basis of her production she took the Perrot-Petipa version which had existed until that of Agrippina Vaganova in 1935. The production had three scenes and the tragic ending was omitted.

Onstage the lack of men could be sensed. Performers of the Musical Comedy Theatre were invited for the roles of Quasimodo and the chief vagrant Clopin Trouillefou. “There are no men even for mime roles,” Nikolai Kondratiev who was at the premiere noted in his diary, “and depicting the modest number of police constables (there were just two) on their night-time beat of the streets and squares of Paris, scattering the crowd from the square and beating Quasimodo, fell to women dressed in male costumes.”

“The class is not heated,” wrote Olga Iordan in her diary, “the corps de ballet and non-dancing characters did not remove their street clothes at the rehearsal; they danced, or rather they made the movements in fur coats, felt boots and gloves. They also did arabesques like that. (...)

“We faced another difficult problem: footwear... They wore out quickly and the dancers had to repair them themselves. They were darned and patched with fragments of silk ribbon found at home... And yet not one performance was performed en demi-pointe, everyone danced en-pointe. It was a struggle, but we danced. When rehearsals were moved to the stage we were faced with new difficulties. The orchestra pit – intended for plays – could not accommodate even the small orchestra we had at our disposal. We had to expand it, removing the first two rows of the stalls. On the stage along the footlights there was a concrete block for the iron curtain – we had to pin it together and fill up the cracks with boards. All that work was done by the workers of the Kirov Theatre under the guidance of Alexander Belyakov (Alexander Belyakov was initially the Assistant Director and later the Deputy Director of the theatre – Ed.).”

Quote after: A. Kryukov. Music during the Siege. Chronicle. Leningrad: Kompozitor, 2002. P. 266

O. Iordan. From diaries // Leningrad Theatres during the Great Patriotic War. Moscow-Leningrad. Iskusstvo. 1948. PP 505–506

La Esmeralda. Scene from the ballet. Olga Iordan (Esmeralda) and Nikolai Shekhmatov (Claude Frollo). Photograph from 1942–1943

Natalia Sakhnovskaya, who danced as one of the friends of Fleur de Lys, wrote in her diary: “We have to do our make-up still wearing our coats, the temperature is low, though the electricity is working, and yet we still have to wear tights and ballet costumes... Our sweet costumiers M. D. Merkulova and A. Ya. Sheinis (Anna Dmitrievna Merkulova, a seamstress and dresser of the women’s wardrobe department, and Khaya Yankelevna Sheinis, a seamstress and knitter of the men’s wardrobe department – Ed.), whose hands have lovingly ironed and sorted all the costumes, keep an eye on everyone, hemming something, lining something else... The girls are so slim and refined in their ballet tunics, shivering from the cold and anxiety. Any warm-ups are in vain, the legs just stay cold... 24 December. We danced the second performance without any fear and with enjoyment. We have made this little stage our own and have come to love our tiny Siege Theatre.”

Olga Iordan recalled that after a performance she received some presents – an onion from an unknown sailor, half a loaf of bread from a serviceman and a bottle of dark cooking oil from the performer Ivan Nechaev.

Dmitry Lazarev, who was present at the premiere, recalled that “during the interval my wife and I went backstage. Olga Genrikhovna met us with a happy laugh – ‘I looked through the peephole, the people had even taken off their mittens so they could clap louder.’”

From 12 December to the end of the war La Esmeralda was performed thirty-one times.

N. Sakhnovskaya. From Siege Diaries // Remembering again… Anthology. St Petersburg: The Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet, 2004. P. 45

Soviet Ballet. 1988, No 3. P. 28

The chronicle features photographs from the Mariinsky Theatre Archive, performers' family collections and the collection of the Central State Archive of Film and Photo Documents of St Petersburg.